Read Time: 2.5 hours, uninterrupted. Too long for anyone to read in full. But selective skimming will cut your read time to just under 2 hours.

As a Kid

The emotional connection to animals has always been there. I’ve yet to recover from the Lad: A Dog movie, books and stories. Same for Old Yeller and Born Free. I was horrified seeing how people would “discipline” their dogs on walks. Viewing animals in cages greatly agitated and deeply saddened me. My one trip to Sea World was an emotional disaster. Accounts of animal-targeted awfulness in books and movies, whether true or fictional, would shake me up terribly. They still do, and now I see or hear them in some form just about every day.

I read Follow My Leader countless times in grade school. In it, a young boy, roughly my age at the time, is blinded by an errant firecracker, leading to him getting a guide dog. I was intensely jealous and, at the time, trading one’s vision for a guide dog seemed to me to be a pretty fair exchange.

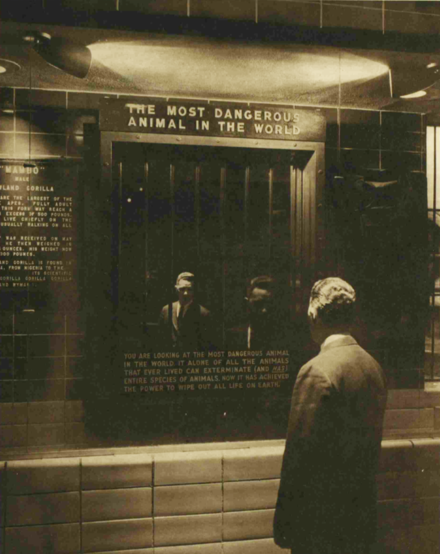

Zoos greatly unsettled me, but from time to time as a young kid it couldn’t be avoided. On some class trip or the like, I found my way to the Bronx Zoo’s Most Dangerous Animal in the World exhibit, which was first displayed in 1963 in the Great Apes House (because that’s where Great Apes live in the wild, in houses).

The exhibit featured a mirror fronted by zoo-like cage bars with text describing the dangers humans pose.

“You are looking at the most dangerous animal in the world. It alone of all the animals that ever lived can exterminate (and has) entire species of animals. Now it has the power to wipe out all life on earth.”

It was later changed to:

“This animal, increasing at a rate of 19,000 every 24 hours, is the only creature that has ever killed off entire species of other animals. Now it has the power to wipe out all life on earth.”

The exhibit scared me then. Seeing this photograph and being reminded of the details of what I had seen 50+ years ago, it scares me now. It has quite the apocalyptical feel and message to it. But I remember also being confused by the zoo’s seeming self-damning admission of how dismally we routinely treat our animals, including, as far as I was and am concerned, by isolating them in cages and artificial “settings” for a lifetime – an entire fucking lifetime - just for our idiotic gawking pleasure.

The Switch Flips

In 1988 or so I managed to squint my way through my first documentary about how we process (i.e., abuse, torture, and kill) animals that we consume. For the first time I allowed/forced myself to experience on a visceral level just how much suffering we cause animals for no justifiable reason, and all kinds of shameful ones. Before, I sort of knew it was bad, but I had no idea at the time it could be anywhere near that bad. And as I now know, it’s so, so much worse.

I had started working as a lawyer a few years earlier. To reward (or console) myself for my miserable 80-hour work weeks, I had treated myself to a “fine leather” jacket, something I’m chagrined to admit I had wanted for some number of years, giving little thought to the process by which this fine leather got from the animal’s body to mine. I (ugh!) loved the jacket.

The documentary finally, mercifully, ended at maybe around 10 p.m. - leaving me reeling. I was living at the time in New York City’s West Village. Appalled by the glaring terribleness of it hanging there in my closet, I grabbed the jacket, stuffed it in a bag and headed some number of blocks over to Sixth Avenue. When I reached the usual array of homeless people camped out on top of the luxury “heated” grates lining our glamorous “Avenue of the Americas,” I handed the bag to the first man I met. I said nothing about what it was, why I needed so urgently to be rid of it then and there, or the life changes to which I had just committed

An Hour with the Gorillas

Gorillas in the Mist just destroyed me. As unimaginable as it was for me back in the late-1980’s when I was first learning about Dian Fossey’s extraordinary work, in 2016 I flew for over 20 hours and drove for 4 days across Rwanda to spend the allotted one hour with the 14-member Hirwa gorilla family in Volcanoes National Park.

Soon after we reached them, while I was still trying to absorb the spectacularness of it all, two adolescents ran past me, each dragging an open hand across my shins, just as we might absentmindedly run our hands along the slats of a picket fence. A bit later, an older adolescent came over, stood next to me as I crouched, looked at me for a few moments, tapped the ribs on my left side three times with the back of his hand, and continued on. This is not a common occurrence, as I was fully aware in the moment.

In all, I was lightly touched by three of them, deeply moved by all of them and profoundly changed by the experience. This one hour was among the most joyful, compelling and transformative events I’ve ever experienced and the enormity of it hasn’t waned, not even a little bit. The trip was instrumental in the further development of my commitment to animal protection and to pouring myself as fully as possible into the work we’re doing today.

I can’t help pausing here to pass on that we discovered mountain gorillas on October 17, 1902. I’m inclined to think the mountain gorillas had discovered us long before but had no reason to let us know. We, on the other hand, and specifically, Captain von Beringe of the German army, welcomed the mountain gorilla into our consciousness by murdering two of them, which he sent to the Natural History Museum in Berlin to be “examined and documented.”

What a shameful tribute to our remarkable indifference to the lives, suffering and death of other beings, including those with whom we share 96% of our genetic sequence. We impose ourselves, stumble upon a new (to us) specious - with a number of decidedly prominent human-like physical and behavioral characteristics no less - and our first order of business is to kill a few to satisfy our curiosity. Things got far worse for the mountain gorillas once people found that, as just one awful example, their severed hands would make saleable ash trays. We, of course, nearly wiped them out but they’re making a remarkable comeback thanks to governmental and conservationist efforts.

When I get discouraged about whether the work we do makes a difference, I think back to Captain Von Beringe’s “how do you do?” execution of those two mountain gorillas. And it reminds me that, left to our own devices, so many animal species wouldn’t stand a chance. It re-focuses me and gets me back to trusting that the work we and our clients do matters.

A Week with Sheldrick's Orphaned Elephants

Elephants forever have been extremely compelling to me. And the more I see, read and learn, the more compelling they became.

In 2019, I had the great fortune of spending a week at the Sheldrick elephant orphanage in Kenya. The orphans at Sheldrick invariably start out by suffering horrific trauma, often inflicted or caused by humans. They watch their mothers being ensnared and slaughtered for their tusks or killed in human-elephant conflicts. Or they're abandoned by the herd following an injury or the emergence of a disorder at birth that prevents them from keeping up. It's all quite harsh. The more fortunate are rescued and taken in and hand-raised by the keepers at the orphanage, with the goal being to return them to the wild.

Even less fortunate babies and adolescents are separated and taken from their mothers, shipped in terror across the world as freight, and enslaved in a desolate existence with no other elephants or sources of comfort contact, often for the duration of their abbreviated lives. Baby elephants may be "trained" into compliance through a process known as “the crush,” which can include being restrained in cruel configurations and relentlessly beaten, sometimes for weeks on end. And then they are neglected. This neglect, trauma, and abuse breaks their spirit and shortens their life expectancy substantially compared to wild elephants, which, under the circumstances, may stand as a stroke of unintended mercy.

With the goal being to return them to the wild, visitors are prohibited from making physical contact with the elephants, except those who would never be able to leave the orphanage, like Shukuru, a ten-year-old (when I met her) female.

Just days old she fell down a pipeline manhole and the herd moved on, having no way to recover her. A passing herdsman heard her cries and, with the help of some passersby and an extraordinary collective effort, he was able to extract her. Other rescuers were determined to kill her for bushmeat, but the herdsman intervened and sheltered her in his home while Sheldrick organized a rescue.

In just that week, I developed a relationship with the head keeper, Philip, with whom I'm still in touch. He sends me videos and photos of the orphans and keeps me up on what's happening with them. The relationship has grown and extends to family and life matters for both of us.

On my last day at Sheldrick, Philip, the other keepers and I embraced and thanked each other for what each of us had brought to the other. Before parting, the keepers started leading the elephants from their home base to the area where they would be spending the day.

Shukuru, who was the last elephant in line, stopped following at a certain point, turned and came back where I was standing with the keepers. We made contact for a few moments and she turned and went to catch up with the others. This was the only time she had done this with me, on that last day. I won’t speculate on what was going on for her in that moment or what prompted her to do this, but it was a life-altering event for me. It strengthened my resolve. particularly concerning elephant suffering.

Shukuru never fully recovered from her initial trauma and, as Philip sorrowfully relayed to me, passed in 2021, 12 years after her rescue and 2 years after I had met her. https://www.sheldrickwildlifetrust.org/news/updates/shukurus-passing

ADP

Joel and I had formed ADP just a few months before my 2016 Rwanda trip. And to say I returned with a heightened commitment and purpose would be a vast understatement. Same for the Kenya trip.

Our organization, our clients and the animals we partner-up to protect are an enormous part of my everyday life (as well as my sleepless nights). Other than my family and the dogs we’ve gotten to live with, there’s nothing in my life that’s provided nearly as much satisfaction or sense of purpose.

In my 30+ years of lawyering, I never owned a suit that fit me. Off the rack, tailor made, take it in, let it out, looser, tighter, longer, shorter, try a cheerier shade of dark gray, it didn’t matter. It never felt right, and it was never going to. It all fits much better now.

David Ebert

Co-Founder - Animal Defense Partnership

December 2022

Epilogue

A Recent Reminder of Why

I recently landed on a Saturday night in a world-renowned hospital’s almost comically overwhelmed ER. And, as you’d expect, the time just flew by - for the entire 10 hours.

Once settled in, I had nothing much to do. There was nothing to read, nothing to listen to and no one to talk to, nothing to watch and nothing to not watch it on. I was tethered to an IV drip and, being deemed a fall risk, forbidden from rising to my feet unassisted and when I took a stab at it, I was upright-shamed. All of the ER’s razzle-dazzle ebbed quickly and I had no idea when I might be sprung.

There I was, confined to a box with absolutely nothing to do. I had no control over the temperature or air circulation. I also was a disregarded bystander concerning when, whether, what and how much I could eat or drink. The prison-grade lighting and unrelenting beeping made sleep impossible. I was also treated to an endless parade of doctors, nurses, staff members, police officers, firefighters, and other patients strolled by. Rudely, I had no say whatsoever in my next revolving bunkmate or which ailments would be suitable. I had no ability to control who gawked and who didn’t or what they would see if they did, owing to the absence of a top sheet or privacy curtain that could provide comfort or privacy. There I was, completely exposed and at the whim of my caregivers.

Around maybe hour five or six, I found myself perseverating on the absolute limits of my endurance. How long could i tolerate being confined to an empty box for every single 10 hours of every single day of the one life I get to live? 9.5 hours. That this or anything similar circumstances could be my permanent state of being was gruesome in the extreme.

I then strategized about the array of tools, techniques, plans, means and methods by which I would just end it all, one of the immediate benefits of which would to finally be liberated that much sooner. And to do the deed in a massively crowded and frenzied ER chock full of our latest and greatest life-saving and death-defying devices, no less. (As many of the self-delivery and assisted suicide enthusiasts among us know, this scenario is not covered in Final Exit, leaving me very much on my own to devise my fail-safe solo conspiracy, to be elegantly executed in a manner befitting my inopportune demise.)

* * *

My ultra-ridiculous gurney-inspired containment-for-eternity fantasy is, of course, anathema to the fundamental freedoms we recognize and defend, including self-determination; privacy; thought and conscience; avoidance of suffering; and so on. To say that the notion that any innocent sentient being could be extracted, involuntarily, from their world, stripped of what we recognize as immutable fundamental rights, and placed in a box for public display – for life – is unspeakably wretched would be to vastly understate it. To even suggest otherwise would be to implicitly endorse practices that we already recognize as catastrophically and horrifically cruel, immoral, inhumane, and inhuman.

Hey, we’re all sentient beings here. We would never inflict such horrors on any other being with our same capacity to experience positive and negative feelings, pleasure, joy, fear, loneliness, dread, hopelessness, pain, and distress. It’s just plain wrong and just not who we are.

No Comments